Tonkotsu ramen, and the things we leave to the experts.

Adapted from: the specialty dish of Fukuoka, Japan.

One of the defining aspects of my personality, something that has followed me like a shadow throughout my life, is that I set arbitrarily challenges for myself. They are often moderately ascetic, like doing the Whole 30, or writing a novella for National Novel Writing Month at night, or not shopping for a year. I do a lot of things to prove to myself that I can. In the words of my osteopath, the first time we met: “You like hardship!” Consider me read.

This character trait manifests often in my home cooking life. I follow novelty like the sun and love a project, which often results in spending a whole day in the kitchen testing recipes and tearing my hair out. Add to this mental pressure cooker the delusional need to to succeed on my first try, because it’s unlikely I’ll make the same thing twice. I don’t know why the universe made me like this.

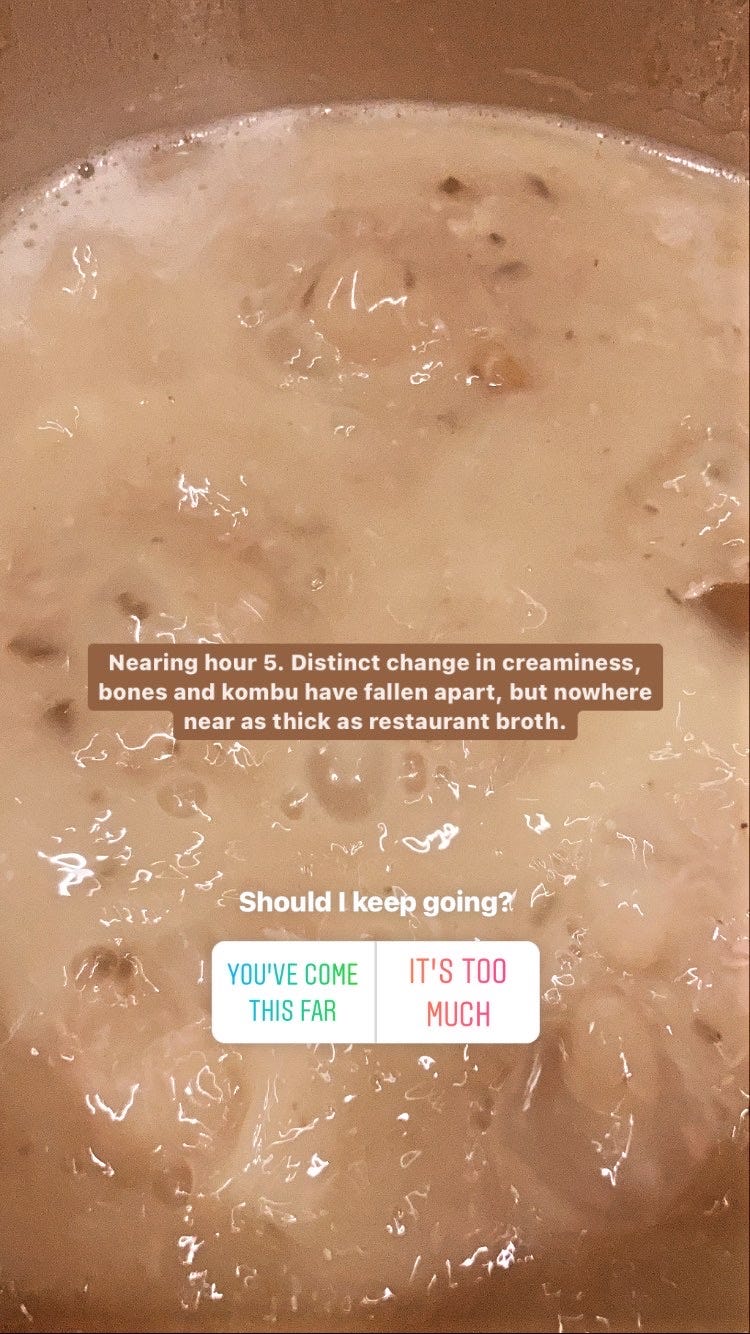

A few weeks ago, I make tonkotsu ramen for the first and last time. Ramen had always been on my cooking bucket list, like pho (to come), something to make once so that I could justify paying others for it moving forward. Between making the cha shu (braised pork belly), nitamago (soft-boiled egg), and boiling down bones for the broth (6 and some hours), it spanned two days, and that’s only because I refused to devote another day to the process and cut the whole thing short. Most tonkotsu broths are simmered for 12+ hours, some up to three days. I am all for doing things the way they should be done, but there are limits to my masochism.

Tonkotsu ramen (豚骨 “pork bone” ラーメン “ramen”), also known as Hakata-style ramen, hails from Fukuoka, Japan. (Hakata is one of the central wards in Fukuoka.) To make the broth, pork bones (and sometimes chicken bones, too, as well as aromatics like green onions and ginger) are boiled aggressively and extensively, until the fat and collagen have been extracted and emulsified. This is what gives tonkotsu broth its characteristic creamy-white opaqueness.

To this, we add a tare (seasoning sauce), which gives the broth its umami and flavour base. This varies by restaurant and region. In Sapporo, miso is the go-to tare flavour; in Tokyo, it’s shoyu (soy-based). Then, you have your toppings: a soft boiled egg, scallions, corn, enoki mushrooms, fish cake, beansprouts, etc.

Fun fact (thanks, L.!): Ramen is a transliteration of the Chinese la mian, or “hand-pulled noodles.” According to The Guardian,

The earliest footprints of ramen in Japan can be found around the turn of the 20th century, as Chinese migrants in areas such as Yokohama, Hakodate and Nagasaki, the first ports opened to the outside world after hundreds of years of isolationism, began selling the soup to construction workers. Back then it was called shina soba, “Chinese noodles.”

Ramen’s popularity was expedited by World War II, after the Americans moved in, and with them, their supply of wheat and lard. From the same article above:

In his excellent book The Untold History of Ramen, George Solt points out that these two ingredients, along with garlic, became the basis for what the Japanese called “stamina food”, belly-filling staples such as gyoza, okonomiyaki and ramen that became lifelines in the scavenger years following the war. Rice harvests were largely compromised by the war, so American flour became the building block for postwar recovery, and eventually the reindustrialisation of Japan.

Like curry rice, ramen is both very Japanese and not at all. It’s an emblematic dish of Japanese culture to the outside world that, upon a closer look, reveals itself to be a product of the country’s political history. This shouldn’t come as a surprise anymore, but it still does, and I’m glad. Without surprise, what is curiosity?

Having made tonkotsu ramen once, I feel content to never attempt it again. Instead, I’ll happily support ramen restaurants, especially as so many are teetering on the edge of permanent closure. [Long, audible sigh.] Now that I understand the work that goes into making it, I feel like all of them could justify doubling their prices*. I feel this way about most things. There should be an augmented reality app that shows you how every item or object is made, by whom, and how long it took. The information would be horrifying and revelatory. Silicon Valley, you can have that one for free.

*The cost of this ramen experiment:

$34 - pork belly, 6ish lbs of pork neck bones

$6 - 4x individual servings of fresh ramen noodles

$4 - estimate of cost of eggs, soy, scallions, ginger, etc.

The recipe yielded 4 bowls of ramen, which means each cost $11. And that does not account for my time and labour!!!

Having said that, this week, I’m linking out to ramen you don’t need to make yourself. Chances are, your local ramen shop could use the support. (If I haven’t sufficiently deterred you, and you do want to try this for yourself, here is the recipe I used. It’s adapted from chef Takashi Miyazaki.) I recommend each bowl wholeheartedly and with gusto. Apologies for the Toronto-centricity.

Three ramens to try in Toronto:

From Ramen Isshin, the Spicy Red Miso Ramen (my absolute favourite, pictured above):

House made chilli oil, Isshin Red Miso blend, wok fried pork, onions, bean sprouts, carrots, wood ear mushrooms, chives, green onions, pork belly cha shu & thick twisty noodles.

From Tondou Ramen, the Okinawa Soba (the bonito broth is so good):

Traditional thick Okinawan soba noodle in a light bonito & pork flavoured broth topped with scallions, pickled ginger, 3 slices of pork chashu, 2 slices of kamaboko fish cake and seasoned seaweed. Served with a side of Koregusu (vodka infused with chilli peppers).

From Sansotei Ramen, the Tomato Ramen (I can’t resist a novelty flavour):

Chashu, Hokkaido scallop, egg, tomato, shiitake.

Happy new year! We deviated from our schedule for a bit because it was the holidays and time no longer exists as a concept. Glad to be back. Hope you’re healthy and staying safe, and I welcome your ideas on new ways to wish people well in 2021.

Until next time,

Tracy 🍜