When I’m cooking a recipe from a culture I know very little about, I’m fairly neurotic about making it exactly as it was written. Sometimes this requires filing the recipe away until I can find a particular herb or an inaccessible spice, a process that—especially when combined with a certain level of laziness—draws out the whole thing for years. I do this in part out of respect for the recipe writer, but also because I want to know what a dish is supposed to taste like, why it occupies the emotional space that it does in a cook’s heart, before I get in there and adjust it to my own preferences. Food writer Genevieve Ko wrote about a similar sentiment earlier this year:

Last summer, as I reflected on how unconscious bias can creep into the kitchen, I realized that I should start cooking by considering what the recipe creator is offering — not by imposing myself on the recipe. By inserting my known likes and dislikes, I miss the opportunity to get to know another person, to see (and taste) her history and culture through her perspective. I want to experience a dish through the person most intimate with it.

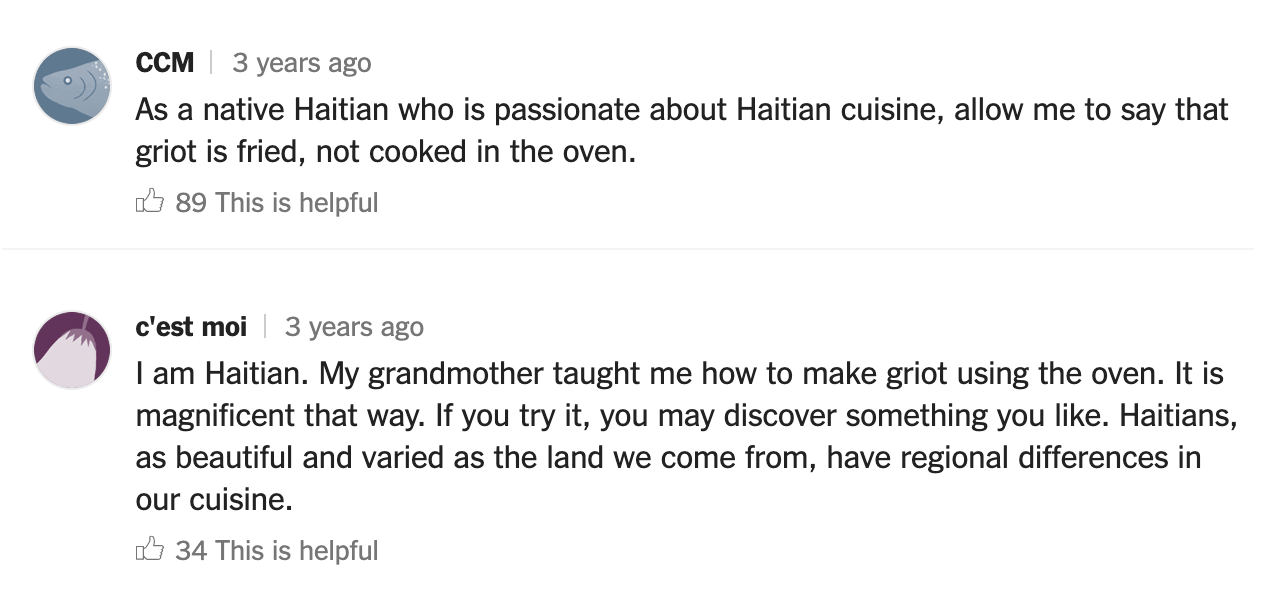

This instinct to honour a recipe, on the other hand, plays into the loaded concept of authenticity in cooking. Does a recipe cease to be true the minute something is altered? Where do we draw the line? Nevermind the fact that any recipe that makes its way to a home cook like me has been tampered with and adapted endlessly—in this case, the original recipe hails from Haitian chef Patrick Celestin, of Celestin’s in Sacramento. Then comes the problem of treating any culture like a monolith. I saw the nuances of what it means to make real Haitian griot pop up in the comments section:

In the words of chef Meherwan Irani, “Authenticity is a construct.” And often, it’s constructed as a lens for a certain gaze: “With the possible exception of barbecue, authentic is really only used in America as a descriptor for ethnic (usually understood as meaning non-white, non-European) restaurants,” writes journalist Kevin Alexander. “Ostensibly to serve as a dog whistle for white people to understand that the food served there caters to them.”

Not that there’s anything wrong with being curious about foods from other cultures. The failure is in the word “authentic” itself, which suspends a dish in a moment in time and space, and does not allow for it to—like any good food should—evolve with its new cultural context, local ingredients, and audience.

It’s also a term that holds different connotations, depending on what type of food we’re talking about:

In a 2019 report on Eater NY, Sara Kay found that when it came to restaurants serving European cuisine, Yelp reviewers associated authenticity with white tablecloths, elegance, and an overall positive dining experience. However, authenticity at non-European restaurants more often meant cheap food, dirty decor, and harried service. White people were allowed to be both authentic and upscale, while cuisine from people of color had to stay cheap and lowbrow to qualify. — Jaya Saxena, “What did ‘authenticity’ in food mean in 2019?”

Authentic to what, and to whom? A question that bears asking, forever.

Making pork griot in my kitchen in Toronto is already inauthentic to the Haitian experience. Marinating it in vinegar and lime juice before sticking it in the fridge overnight is an adaptation that results from privilege, of not having to wash my meat in sour orange juice out of food safety precaution. So I broiled the meat! Forgive me, griot traditionalists. The meat still came out perfect—browned and crispy in all the right places, the tenderness intact. Ate it with so much pikliz, it made my teeth ache.

Recipe notes:

Haitian Pork Griot

Recipe from Patrick Celestin, adapted by Melissa Clark for NYT Cooking

I made this recipe exactly as is. It was tangy and amazing.

Thank you for the recommendation, Anna!

Traditional takes on griot:

Via Djanan Kernizan and Emily Stevens at Gusto Journal, a lime-marinated version served with fried plantains. “To me, the term griot translates to family, home, and ethnic roots.”

Via the food blog Arousing Appetites, a detailed history of griot and the addition of a spicy sauce called “sos Ti-Malice” - the leftover marinade liquid reduced with alliums and hot peppers.

Via CaribbeanPot.com, a fried version which comes with the excellent recommendation of making a sandwich with the griot.

This is my first foray into Haitian cooking. If you have any you love, please send them my way.

Until next time!

Tracy