Artichoke pasta, and the changing of taste.

Adapted from: pasta con carcifoli e pancetta, the Tuscan way.

I am generally an equal opportunity eater. I’ll try most things once, provided it’s not an organ that still resembles itself when it’s served, or something that used to contain poison. That feels reasonable to most people, and rarely does it become a point of contention when sharing food at a restaurant, or deciding what to cook for a dinner party. But there’s one everyday exception to the rule, a vegetable I’ve avoided my whole life, and that is the artichoke. My parents used to eat them all the time, right from the can. I could never stand the smell.

Well, no longer. As of this week, I love artichokes and can’t get enough of them. Taste is funny that way. Sometime in the last year there was a changing of the guard on my taste buds, and the results are remarkable. As a lifelong cilantro lover, I can barely tolerate the taste of a single raw leaf now. I can’t tell you how the taste differs in itself—is it soapier? more pungent?—just that, well, now it revolts me slightly, to my chagrin. And the inverse has happened with artichoke.

The whole thing feels serendipitous. I was watching the Rome episode of Stanley Tucci: Searching for Italy when I found myself wistfully wishing I liked them, as I do whenever people exhibit intense enthusiasm for something I feel very little towards. (See also: sports as entertainment.) Then, Anna sent me a recipe she loved, an artichoke-forward pasta with a fun noodle shape. Then, it was artichoke season in Little Italy, and I started seeing them at fruit markets everywhere. Suddenly, I felt compelled to do what I thought I’d avoid my whole life: prepare a fresh artichoke.

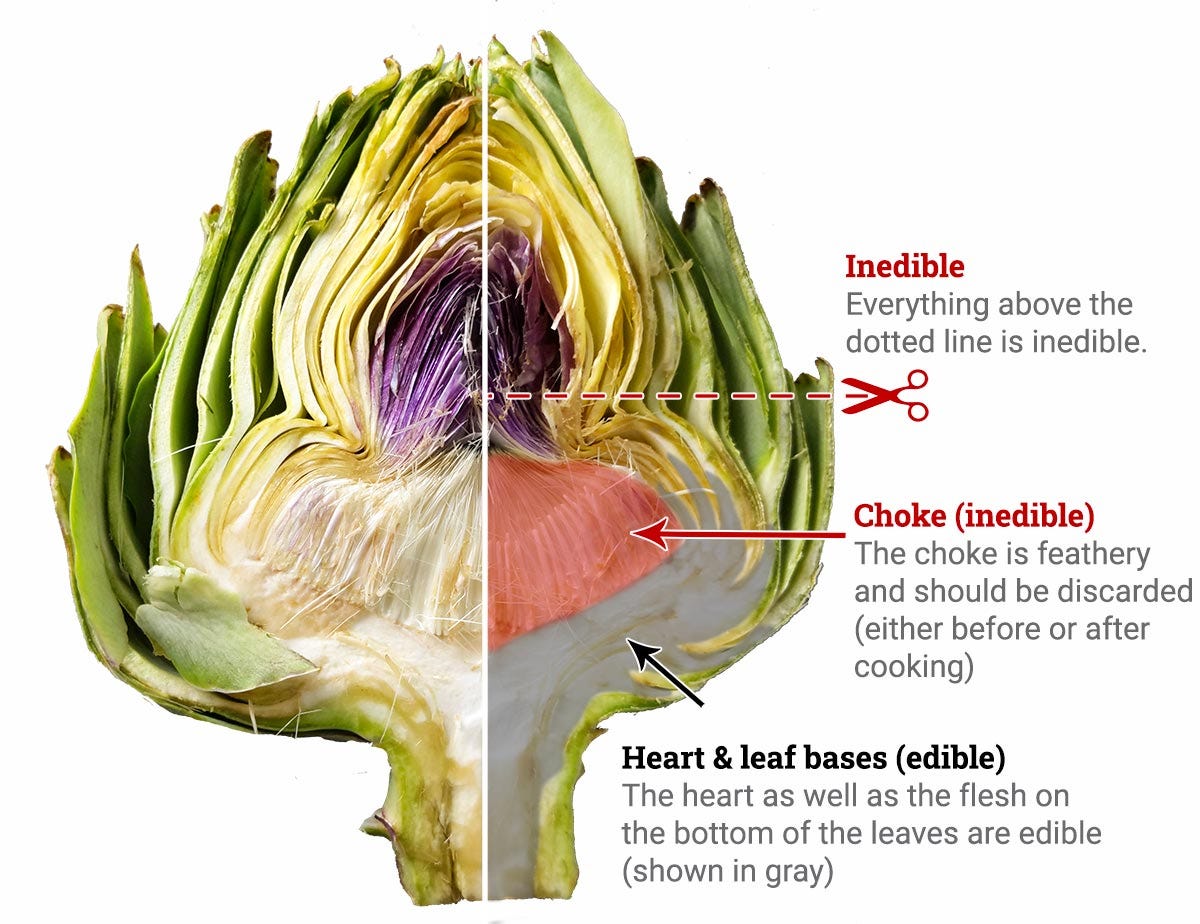

The artichoke, as you might surmise from simply looking at one, is not a tender vegetable. As a variety of thistle, it is thorny at the tip, rough around the edges and a choking hazard at its core. At least 85% of the ones I bought went straight into the compost bin—the tough outer leaves, the fuzzy choke, the inedible purple flower hidden within. What’s left are the edible bits, the stuff people seem to go crazy for: the artichoke heart and the tender stem base.

It’s one of those foods that, like geoduck or sea cucumber, begs the question: who thought eating this was a good idea?

Or is its elusiveness central to its appeal?

Artichokes, the myth

My friend Carter is a perfumer and recently released an eau de parfum formulation of a perfume called Spite, which features an artichoke absolute. I thought about him as I stripped these artichokes, because it is truly a spiteful vegetable, with an even more spiteful origin story:

According to Greek myth, the artichoke owes its existence to the philandering Zeus who—on a visit to his brother Poseidon—spotted a gorgeous girl, Cynara, bathing on the beach. He fell instantly in love, seduced her, made her a goddess, and took her back with him to Mount Olympus. Cynara, however, lonesome and missing her mother, soon took to sneaking home to visit her family. This duplicitous act so infuriated Zeus that—in a fit of temper worthy of Caravaggio—he tossed Cynara from Olympus and turned her into an artichoke. The modern scientific name for artichoke—Cynara cardunculus—derives from this luckless girl.

Artichokes, the history

Despite putting up a good fight, artichokes have been prepared and consumed for millennia. According to NPR, it was first nurtured by the Arabs in the early Medieval period:

Historians believe that artichokes were cultivated by North African Moors beginning about 800 A.D., and that the Saracens, another Arab group, introduced artichokes to Italy. This may explain how the Arabic al-qarshuf — meaning "thistle" — became articiocco in Italian and eventually "artichoke" in English.

From there it was supposedly introduced to the French by Catherine de Medici, and brought over to North America in the 1600s. And, according to a piece in The Kitchn, “It’s also the subject of a little-known chapter in the history of organized crime. Almost a century ago, New York City mobsters weren’t just bootlegging, gambling, and loansharking. They were engaged in another shady million-dollar operation: artichoke racketeering.”

I’m glad I tried making fresh artichoke once, if only to understand all the hoopla.

Is it worth it? Hard to say. Depends on how much effort you like to make for your rewards. But was I surprised by how much I loved it, and looked forward to the leftovers? Thoroughly.

Artichoke pasta, the recipe

Pasta With Artichokes and Pancetta, via NYT Cooking

I used vermouth and mint instead of white wine and parsley here—both choices that I think complemented and accentuated the sweet, herbal notes of the artichoke. It was incredible and I would absolutely make again—except next time, I’ll substitute fresh with canned artichokes and see if I notice the difference in flavour.

Here is a similar recipe from Italian food blog Profumo di Basilico, for comparative purposes.

Have you noticed any abrupt changes in your own eating preferences? Tell me about them!

Until next time,

Tracy